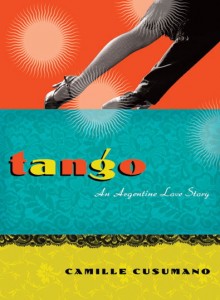

An excerpt from Tango, an Argentine Love Story

An excerpt from Tango, an Argentine Love Story

“The stillness shall be the dancing and the darkness the light.”

-“East Coker,” T. S. Elliott

” . . . Happy is what I feel as I cross town in a taxi with my five suitcases in tow. I love that it’s summer in January here, and that I can expose a lot of skin and wear sandals and halter tops day and night-something that would lead to serious hypothermia during San Francisco’s summer months. The heat wallops me as I step with my five bags from the air-conditioned taxi at French, an auspiciously named street in the Recoleta Barrio. I take it as a nod to my lifetime as a Francophile. I am renting the eighth- floor apartment from a woman, Irina Larose, a tango dancer who lives in San Francisco. The apartment she owns is a sparsely furnished one bedroom that has no air-conditioning and no TV, for which I’m relieved. It’s about five hundred square feet, bright and airy. Its finest assets are a blond hardwood floor and two small balconies, one off the living/dining area, one off the bedroom. I keep their glass doors wide open day and night, and along with the two ceiling fans it creates for that breezy living-in-the-outdoors feeling I covet. My surroundings are soothing: the sights and sounds of busy neighbors’ lives in surrounding high rises. I’m alone but not lonely.

A five-by-three-foot panel of Picasso’s Guernica hangs over the wooden table where I will work and eat. It takes me by surprise. Its dark theme (the 1937 Nazi bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War) reminds me of my late friend and mentor, Anne Hoffman, who was an American Communist and political activist against the inhumanity and destruction that pushed Picasso to depict the ravages of war in this, one of his most famous paintings. Anne once told me that she first saw Guernica when she was on a date at San Francisco’s Palace of the Legion of Honor museum with the maker of the atom bomb, Robert Oppenheimer.

Anne inspires me still, and now having Guernica above the table where I eat and work, I feel as if she’s watching over me.

I’m happy to be living alone again. I am happy even during the day. Even outside the circle of tango. Not just the skin-deep happy that I put on for social settings. It’s the deep contentment I found as a quiet child who loved her own company. It’s the “zone” or “flow” of the artist and creator. My “medicines” are working.

Like a true Argentine, I quickly become attached to my barrio, its quirks and its purveyors. There’s my skeleton-key maker. He leans out a street-level window of a room with an old linoleum floor. There’s Cambalache, who fashions my lumpy hand-rolled empanadas, and Nonna, from whom I get my cookie-cutter ones. Adriano, the cobbler, fixes my shoes and handbags and would love to cobble me a pair of tango shoes. When I pass by he never fails to step out to kiss me on each cheek and shoot the breeze. He reminds me of some South Philly guys I’ve known, and I’m dying to do my best Rocky Balboa-“Yo, Adriano!”-but it simply wouldn’t translate and so I can only amuse myself with my impulse.

There’s Dany, my pasta maker. “Dany,” I tell him, “your pesto sauce is so flavorful, you must be Genovese, am I right?””No way, I’m Spanish all the way,” he says proudly. “In Argentina, 80 percent of the pizzerias, pasta shops, bakeries, hotels, and garages are owned by Spanish. The Italians do the construction and metallurgy.”Hmmm, I’ve got to wrest back some of that claim for my heritage. “Well,” I say, “but the bakeries don’t have cannoli and tiramisu.”

This gets Dany where he lives. “Yes,” he hangs his head, “you need Mmascarpone cheese and our bakers cannot afford it, it’s too expensive.” I feel like I’ve kicked a man when he’s down. Because of the 2001 financial crisis, many people can’t afford simple designer cheeses or gourmet foods, that we North Americans take for granted, so they’re in short supply. I buy a whole kilogram of his red pepper linguine.

But Recoleta residents can afford paseadores to walk their dogs, so my barrio is full of mini cattle drives, as I come to call them. The paseadores ride herd on as many as twenty-five well-behaved canines on leashes, a comical sight to see as the well-groomed charges strut the busy streets. The plazas and parks along Libertador are filled with every race of dog-either running free or tied to posts. Within my first few weeks in Recoleta, I’ll see more unchecked doggyie sex than I have in my life-which may be why Buenos Aires dogs are the happiest in the world.

I have a set route several mornings a week to my swimming pool at American Sport gym on Charcas. I always take Laprida so I can pass the bomberos, firemen, who are way more sexy in their black lace-up boots, form-fitting attire, and oh, those velvet French tams, than their North American counterparts. Invariably, I share sidewise glances with two or three of them as they stand guard at their red fire engines.

I buy El Clarin every Saturday from the same kiosk, because that’s the day it has the Spanish New York Times-in-Spanish insert. I slow my steps every morning as I pass bmy the sidewalk flower stalls that also sell incense, one in particular that leaves an aftermath of rain showers. The booths are gardens laden with bouquets. For a buck fifty, I sweeten my home with jasminea, freesia, or daffodils.

I frequent the small produce purveyors and the mom-and-pop supermarkets run by Asians; Chinese women who speak less Castellano than I do run the beauty salon-cum-masseuse massage parlor on French.

Living in my new barrio, I realize my eyes are fresh again. I notice the rapture of others. The woman who irons clothes in the Laundromat, the man who sells loose herbs and spices, and the flower vendors. What they all have in common is a gourd of matée in their palms and a thermos of hot water nearby. Through the gold and silver bombilla, or metal straw, they sip their elixir with a contemplative look and air of mystery befitting Sherlock Holmes and his pipe. Argentines talk of their matémate as if it were a companion.

I drew back the first time I sipped it, but I’m a different person now. Amalia, one of my new Castellano professors (I’ve added two to complement Mariel), initiates me. She grabs a fistful of my mate leaves and shows me the little palos (stem sticks) that add a dimension of flavor. “It’s a question of personal taste whether you prefer maté with or without palos,” she says.

Amalia loads the calabaza gourd with the leaves, three-quarters full, covers the gourd mouth with one hand, inverts, shakes, and strikes it once with her other hand. She discards the fine powder that rests in her hand. She shows me how to slope the leaves in the gourd so as to not wet them all each time we add fresh water. We heat, but do not boil, the water. I love the blossoming aroma as we moisten the leaves. I sip through the bombilla. Then Amalia adds hot water and it’s her turn. I love that that she does not wipe off the bombilla. This time it tastes nothing like turpentine. I taste naturally sweet things like artichokes and asparagus and a robustness of baked potatoes. I get a whiff of mountain misery or witch hazel, an aromatic plant that grows in the high Sierra. What I really taste now that I know them is the pampas that stretch for an eternity from Buenos Aires. I am becoming Argentine, and I am opening up to new ways of tasting rapture.”

“The stillness shall be the dancing and the darkness the light.”

-”East Coker,” T. S. Elliott..That caught my thoughts, very deep yet very true.Your story, sounds good to me.